If your portfolio includes stock options or restricted stock units (RSUs), you may be wondering if it matters where you live when there’s an income event—in particular vesting and exercising. The answer is that it matters both where you live and where you work.

If you live in California, then you’re taxed on your worldwide income. There may be an opportunity to claim the other state tax credit in rare circumstances, but the more likely outcome is that you’ll owe tax on all of your income. For this reason, it’s prudent to evaluate the potential benefits of moving before exercising your deferred compensation.

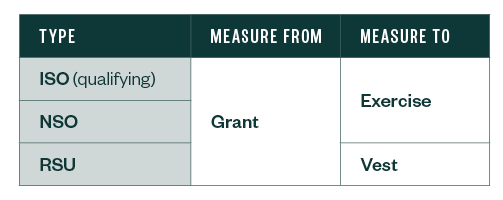

Deferred Compensation Types

There are three common types of deferred compensation:

- Incentive stock options (ISO)

- Non-qualified stock options (NSO)

- RSUs

Incentive Stock Options

Generally, there’s no taxable income event either at grant or exercise if the requirements of Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 422, Incentive Stock Options, are met. There may, however, be an alternative minimum tax (AMT) event in some circumstances.

There’s capital-gains recognition when the stock is sold, presuming holding period requirements are met. The annual limit is $100,000 of ISO income based on fair market value at the time of the grant. Any exercisable amount over the $100,000 threshold in a calendar year is treated as an NSO and may be subject to AMT. If the sale doesn’t meet IRC Section 422 rules, it’s treated as a disqualifying disposition.

Non-qualified Stock Options

In contrast to ISOs, NSOs are typically taxed on exercise at ordinary income tax rates. The taxable amount is the difference between the fair market value at exercise and the option price. If the stock is held after exercise, there may be capital-gains treatment available for the ultimate sale of the stock.

Restricted Stock Units

Unlike ISO and NSO treatment, the focus is on the vesting date for RSUs. The taxable amount is wage income, which is measured by the fair market value upon vesting minus the amount paid for the RSU.

How to Determine California Taxable Income

California Treatment Measured by California Workdays

It’s worth noting there are additional limits on qualifying dispositions in California, including the following:

- Continued employment with issuer

- Timing of transactions

- Option price can’t be less than the fair market value at grant

Other states have different measuring rules, so verify the state-specific rules for any state in which you’ve spent working days when determining treatment.

Measurement of California Taxable Income

California taxable income = California workdays/Total workdays

For an NSO, for example, total workdays would encompass the period between the grant date and exercise date.

How to Calculate California Workdays

Counting workdays is where it gets a little more complicated. The definition of a workday isn’t as clear as it could be and because there are substantial legal reporting requirements for an employer to report income, you may find your employer leaning towards a cautious interpretation.

Most of the regulatory language on the individual side was written before 1990, when workforce mobility was a less common practice. There is some helpful guidance in IRC Regulation Section 17951-5(b) that reads, in part, “The total compensation for personal services must be apportioned between this state and other states and foreign countries in such a manner as to allocate to California that portion of the total compensation, which is reasonably attributable to personal services performed in this state.”

Put another way, any work for which you’re paid that is done while you’re physically in California is treated as California taxable compensation.

Employer Reporting

Add to that the complexity of how work is reported by an employer. For example, if you’re a Bay Area–based employee that travels to Portland, Oregon, for a holiday weekend and you work while you’re in Portland, it’s likely your employer will still treat that work as California-compensated time for ease of administration.

In contrast, if you were to move to Portland with your employer’s agreement, then the wages should be reported as Oregon wages and subject to both state and local taxes accordingly. The reporting of the work complicates the workday counting and can add to the necessary record-keeping in the event of a state tax agency audit.

More Responsibility May Equal More Workdays

Equally important to this analysis is determining what the total workdays are for purposes of establishing the denominator. For example, if your employer has a work-week policy that defines the work week as Monday to Friday with certain holiday exclusions, then that reduced number of workdays in a calendar year that occur between the grant date and the exercise date will serve as the denominator. For someone with greater responsibility, the work week may be all seven days or even all 365 days.

This calculation of total workdays becomes more important if you want to move out of California.

What Happens When You Move

If your employer gives you the opportunity to move, doing so may provide an opportunity to cap your number of California workdays and secure significant tax savings. If your number of total workdays is fixed, then you can calculate the ratio to determine potential tax savings.

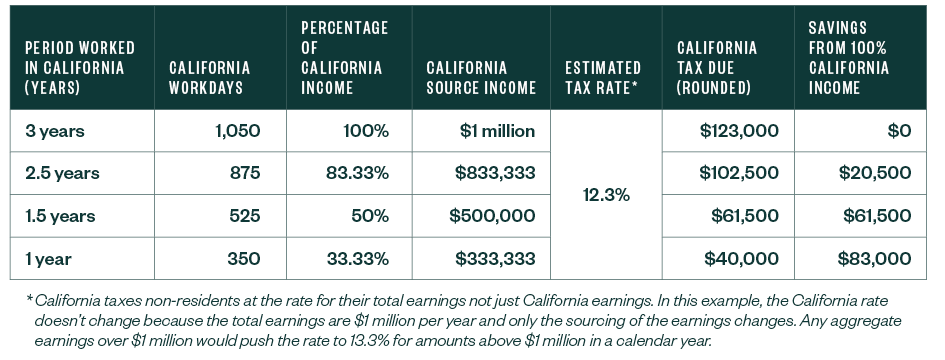

For example, Employee R is a higher-level employee who works seven days a week. Employee R gets an option with a predetermined three-year exercise period. They take 15 days off per year for personal leave per their contract, which leaves 350 workdays per year. Over three years, this is a total of 1,050 total workdays.

For simplicity, the example will presume the fair market value at exercise results in $1 million of total taxable income for Employee R. Let’s see how much Employee R could save if they moved out of state during this three-year period.

Example: Employee R’s Taxable California Workdays

As you can see above, moving out of state towards the end of the measuring period can still provide significant California tax savings. Changing your residency to another state even earlier may increase your potential tax savings.

Changing residency takes time because it requires severing ties from your current state while creating similar connections in a new state. State revenue agencies will audit your residency transition in an effort to claw back income to your prior state of residency, arguing you never severed your prior residency. These audits evaluate your connections to your prior state in contrast to the connections you have built in the new state and usually consider the following:

- Housing

- Physical time spent in the new state versus prior state

- Personal property

- Care providers

- Reason for the move

If you’re considering a move, it’s worth the investment to speak with a tax advisor knowledgeable in residency determination and sourcing rules.

Does Measuring Value Matter?

A recent case before the California Office of Tax Appeals (OTA) saw a taxpayer attempt to argue a greater amount of value was accrued after their exit from California than during the time they lived in California. They provided charts of the stock price mapped against their days in California versus their days out of California. The stock charts showed the stock price increasing significantly after their move out of the state.

In the view of the OTA, the taxpayer couldn’t prove either that their efforts while out of California single-handedly resulted in the stock price change or that the stock price changed because they moved out of California. Without evidence to more fully support the taxpayer’s position, the OTA defaulted to the standard used by the Franchise Tax Board to count days worked in California over total number of days (as described in the chart earlier in the article).

While there may be a future case that changes this approach, for now, the day count application described above is the likely method the agency will use to determine the California-source income component.

What About After Exercise?

The sale of stock is typically sourced to your state of residence. Even if you’re a California resident at the time of exercise, for example, you can change your residency prior to sale of the stock.

If you successfully change your residency to a new state before selling the stock, then the income from the sale will be sourced to your new state of residence. Depending on the appreciation that occurs between the exercise event and the ultimate sale of the stock, the tax savings on this second tranche of income could be even greater than the savings at exercise.

There are many factors to consider when measuring the reportable value of your deferred compensation plan if you change residences during the exercise period. Keeping a workday count for each of your stock options or RSUs and defining workdays with your employer upfront will likely result in less confusion later.

We’re Here to Help

For help determining potential tax savings from moving out of state before an income event, contact your Moss Adams professional.